And Then Came Giotto

I am not an art historian; far from it. I don’t even claim to be a serious student of art. And yet, it is impossible to live in Italy and not develop a profound appreciation for art. There are museums full of ancient art – Etruscan and Roman – displaying artifacts from those eras, from tiny jewelry pieces to funeral urns, mosaics, and classic statuary. And though there were also Roman painters, the examples that have survived are relatively few. In contrast, paintings from the late Medieval (Middle Age) and Renaissance periods fill Italian churches and museums. The differences between the two eras can be appreciated by even an untrained observer like myself.

Madonna and Child ca. 1300 artist: Duccio. (photo from Wikimedia Commons Public Domain). An example of painting from the Medieval era.

Prior to the Renaissance, Medieval paintings were characterized by religious subjects, often a single figure filling the center of a painting. The figures were flat and the faces often expressionless. The human form was not natural looking or sensuous. These were icons, not neighbors.

Backgrounds and perspective were not very important components of medieval painting. And all that gold! Gold shows up everywhere in Italian art of the middle ages. In backgrounds, in halos, in elaborate detailing. Imagine how that gold appeared – as the richness of God, the divine light – and also, perhaps, an symbol of the wealth of the patron or church who commissioned the work.

In contrast, paintings from the Renaissance era (1400 – 1600 AD) make wonderful use of perspective and often place subjects in natural settings. The figures are realistic, their human-ness evident. The clothing drapes and swirls, the faces show a full range of emotions. The subjects are still largely religious, though portraits were also painted, usually for wealthy patrons (think of Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, painted in 1503). The names of Renaissance artists are familiar: Donatello, Da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael being perhaps the most widely known artists from the 1400’s.

An unfinished Da Vinci portrait painted between 1500 - 1505. La Scapigliata (the word scapigliata refers to her disheveled hair) hangs in the National Museum in Parma, Italy. The difference between this Renaissance painting and earlier Medieval ones is pretty clear!

And in between the two periods, the Medieval and the Renaissance, came Giotto di Bondone (1267-1337). Giotto was that rare artist who was appreciated, even famous, during his lifetime. He even merited a mention by his contemporary Dante in The Divine Comedy.

Giotto revolutionized Italian art, creating life-like figures and placing them in more natural settings. Giotto’s figures show a full range of emotions through their facial expressions. No flat, lifeless saints and madonnas here! Giotto’s scenes are populated by people who look like the neighbors down the street (at least what the neighbors would have looked like in 1300). His men are placed in realistic poses and settings, his ladies have (gasp!) breasts over which their garments drape. His angels fly, his flames flicker. And while the saints still have halos of gold, their clothing is colorful and the background is the most heavenly blue.

Panel # 34. Weeping over the Body of Christ. Scovegni Chapel.

Sadly, much of Giotto’s work has been destroyed, by time and by fire. Of the works that remain, the Scrovegni Chapel in Padova is Giotto’s capolavoro (masterpiece). A chance to see the frescoes there was the main reason for my trip to Padova last fall. The church is small and intimate, built as a private chapel for the Scrovegni Family. The frescoes are in wonderful condition, the figures beautiful, and the colors spectacular.

Panel #35. The Resurrection

The frescoes wrap around the chapel, in a three-tiered series of panels, telling stories from the life of Joachim and Anne, Mary, and Christ. The scenes are full of life, there is movement and emotion, the figures pull you in to their story. Through it all Giotto proves to be not just an accomplished artist but a master storyteller as well.

Panels #8 (Presentation of the Virgin), 21 (Baptism of Jesus), and 33 Crucifixion (top to bottom)

The far end of the chapel has the largest scene - the Last Judgement. It is stunning in both its beauty and its brutality.

To the left, heaven. To the right, a hell that is terrifying!

Look closely and you will find Enrico Scrovegni, offering up the chapel in atonement for the sin of usary (the Scrovegni family were money lenders). This is no doubt an attempt to avoid Giotto’s graphic depiction of hell.

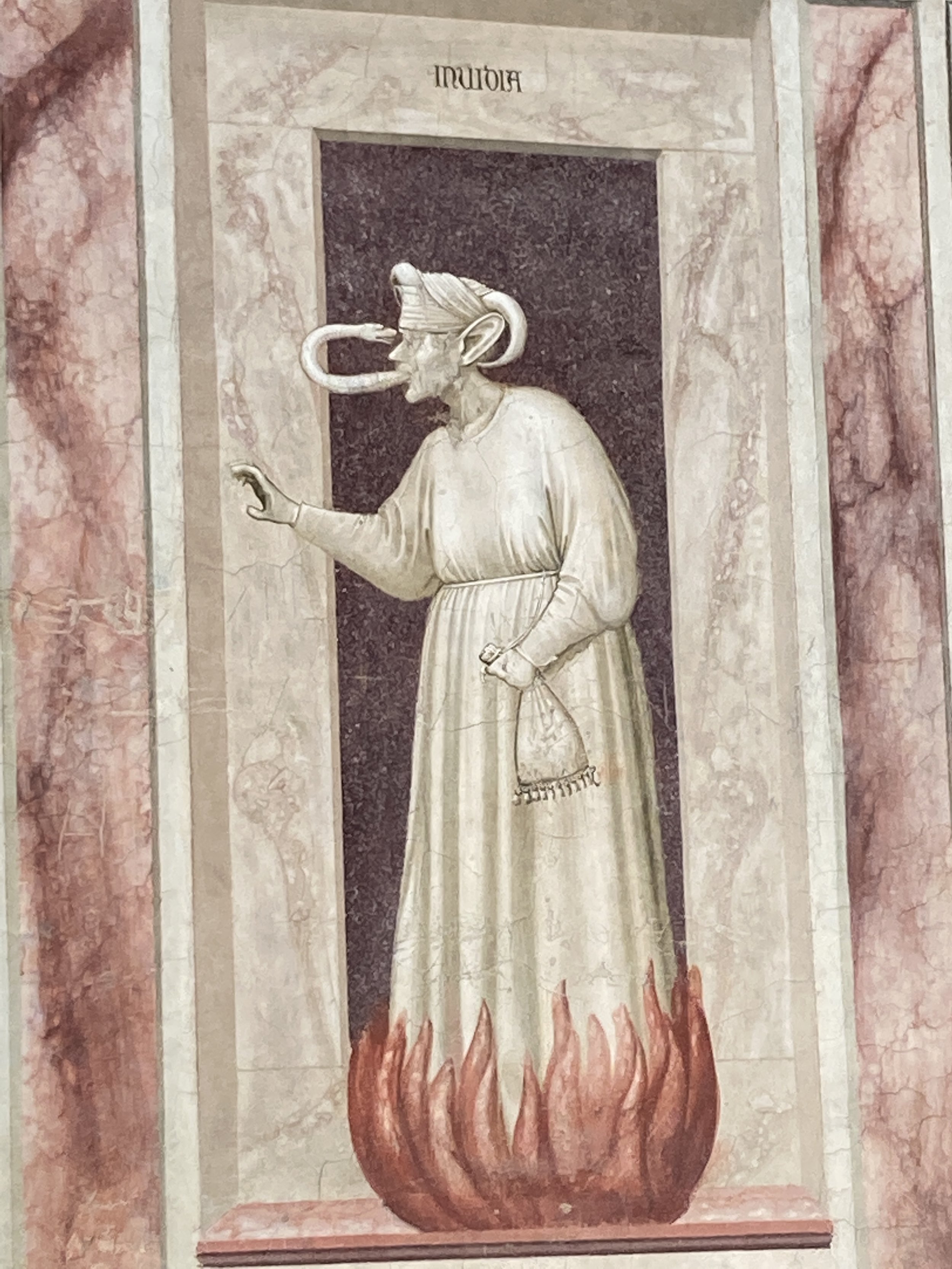

Aside from bible tales, the allegories of Virtues and Vices are fascinating. Simplistic in design and color compared with the rest of the frescoes, without much adornment, the contrasting figures are as relevant and thought-provoking today as when painted in the early 1300’s. Pictured below (left to right): Hope, Envy, Justice, Despair.

The Scrovegni chapel is simply astonishing (my photos can’t capture its majesty). One does not have to be an art historian, a religious scholar, or even a believer, to appreciate Giotto’s artistic brilliance and the power of these frescoes. And for anyone with an interest in art, or simply in beauty, the Scrovegni Chapel in Padova is an experience not to be missed.

Detail from panel #33. The Crucifixion

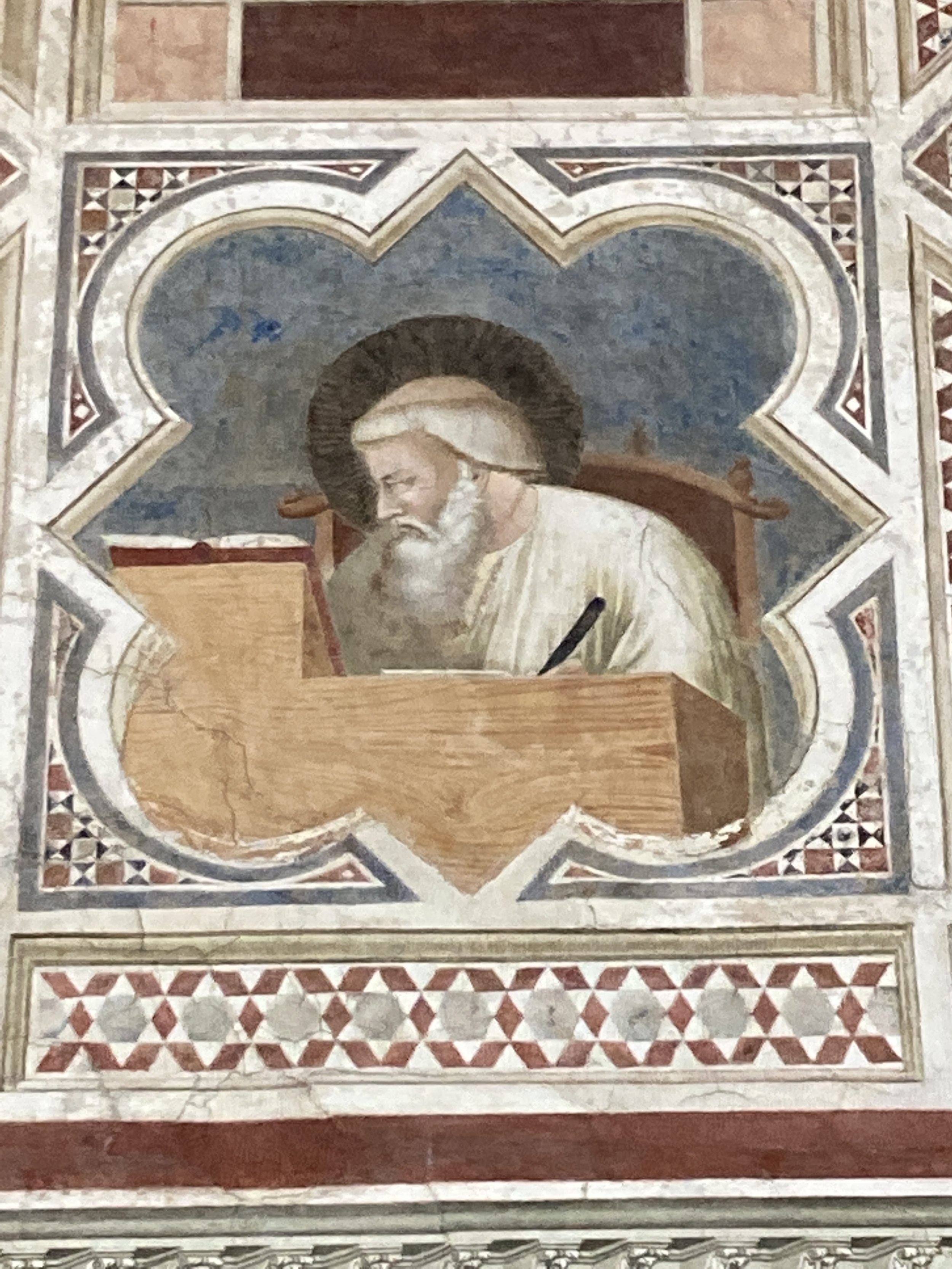

Even the smallest decorations - such as these quatrefoils - have incredible detail and depth. I could spend hours here looking at everything from the largest scene to the smallest detail. I think I’ll need to go back to Padova before too long.

Note: The Scrovegni Chapel is open to the public with advanced reservation tickets only. Before entering the chapel itself there is a short video (with subtitles in English) which gives a good history of the chapel. Admission is limited to about 25 people at a time with a time limit in the chapel of 15 minutes per group. A short time, but well worth it and sufficient to see this small space (especially after some pre-visit reading).